Movement and Ideology in North by Northwest & The Limey

One of my top five favorite films, The Limey, turned ten this year, and independently of that started popping up on the pop-culture radar again in a few different places. First in January on Elvis Mitchell’s wonderful podcast The Treatment, filmmaker Steven Soderbergh described his newest film, The Girlfriend Experience, as his most “Limey-like” film since the original. It’s about an elite call girl working in the pre-election hubbub of October 2008 and stars real-life porn star Sasha Grey. Then recently on The Onion’s awesome “New Cult Canon” series (which last week canonized another favorite of mine, Eyes Wide Shut), critic Scott Tobias added not just The Limey but also the film’s DVD Commentary track to its stellar lineup of films.

It was watching The Limey’s DVD commentary several times that spurred me to begin thinking about it in relation to another film I love, Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. In 2001 I was taking a course on Hitchcock and proposed an extended comparative essay about the two films as my final project. Most of the introduction is dry and overly academic, but the following paragraph cuts to the core of my interest in making the comparison:

Some of the most heated debates of the ’60s/New Wave were Marxist-Capitalist debates, but in these two films Hitchcock and Soderbergh actually visualize these opposing ideologies by consistently placing them in formal opposition to one another and moving their characters between them. North by Northwest, made in 1959, came at a cusp point of the Atomic Age amidst the post-WWII prosperity in America, and its finale, in which both Communism is thwarted (though it’s not said outright) and a marrage is made, wreckons with these twin late-‘50s predicaments. The Limey, made in 1999, came after the end of the Cold War and amidst a wave dot-com prosperity in America. That the Marxist is a villan in one and a hero in the other speaks volumes about these thrillers. That both films are thrillers helps determine exactly how. Again and again, Soderbergh and Hitchcock use the idea of exchange over time, and, more importantly, over space to discuss Marxist and Capitalist ideologies. By coupling movement — which is concerned with the formal kinetics of the characters, camera, and shots — with ideology — which is concerned with the social implications of the films’ content — both directors formulate a relationship between the way things move on screen and what they ideologically represent.

The finest parts of the essay, however, are not these broader theoretical constructions but the two sections that work hardest to closely observe how these films move, how their directors work with the camera, and how their editing schemes organize the scenes and story. This is done first on a formal level and then on a more narrative level, as the each of the films’ characters and settings are aligned with different types of transactions, both political and economic. The essay’s methodological cousin is Frederic Jameson’s worthwhile high-wire analysis of Hitchcock’s film, “Spatial Systems in North by Northwest,” available in its entirety on Google Books here. — RG

Types of formal movement

Movement here constitutes these formal spatial dynamics:

- How the characters move concretely within the film world;

- How they move within the frame of the screen;

- How the camera moves; and

- How the editing moves (or transitions) from one shot to another.

Within the film world, Jameson suggests that the characters in North by Northwest travel from one “scenotope” to another and that these “scenotopes… [identify] each new episodic unit with the development of a radically different kind of concrete space itself, so that we may have the feeling of a virtual anthology of a whole range of distinct spatial configurations….” The Limey’s plot is similarly episodic, and its spaces are equally distinct, although the totality of each “episode” is much more broken down because of the film’s unusual editing scheme, which I will discuss later.

A list of shared scenotopes in the two films includes, but is not limited to:

a hotel room

a Modernist house

a famous cliff side

a coastal road

an airplane1

In terms of movement across the frame, characters may move side-to-side, top-to-bottom, or diagonally. We see all three in both films. Thornhill must cross from left-to-right on two occasions: once to meet the farmer on the other side of the county road, and again to meet Eve Kendall on the other side of the pine grove.2

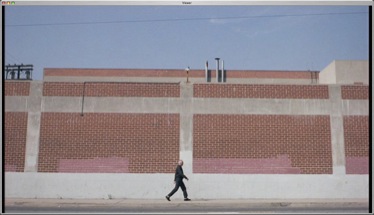

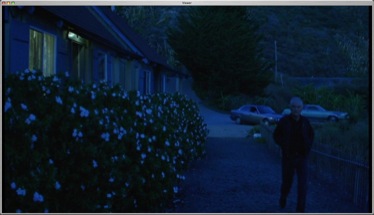

In both cases, Hitchcock emphasizes the distance Thornhill must travel by framing the characters at absolute extreme edges of the screen. As Jameson notes, the space is so extreme that certain audience members may be forced to turn their heads in order to perceive each character as they speak. Moreover, Hitchcock emphasizes the “crossing” of Thornhill in both cases by placing a central obstacle in Thornhill’s way. With the cornfield, there’s a road. With the pine grove, there’s a tree that nearly splits the frame in half. Wilson also makes the long journey from left to right in as he approaches a sketchy warehouse to confront Terry Valentine’s downtown goons. Because the person Wilson’s meeting is not immediately visible, Soderbergh protracts his journey by slowing down the film speed and intercutting the sequence with footage from the discussion during which Wilson recalls this approach. The image itself recalls one of Raymond Chandler’s, which Jameson cites in “Allegorizing Hitchcock” to underscore the uncanniness of the American everyday to a European émigré. Chandler writes, “He got out of the car and walked across the sun-drenched sidewalk until the shadow of an awning over the entrance fell across his face like the touch of cool water.” This is precisely the shot, blown out and stark as Wilson crosses the long wall of the building only to be turned a sea-watery green by the dim light of the fluorescents inside. As one compares the films more closely, shared relationships between screen movement and scenotopes proliferate: characters fall top-to-bottom down the cliff sides, and they move diagonally across the cantilevered patios of Modernist houses.

Equally important is the movement of the camera itself. One of the first camera movements in North by Northwest occurs when Thornhill catches sight of Van Damme’s henchmen in the Oak Room of the Plaza Hotel. The camera tracks from Thornhill’s drinking companions, seated across from him, to the two smirking henchmen and then back to a much tighter shot of Thornhill. The same kind of camera movement, ocurring at the shock of sighting two mysterious men, is used in The Limey, when Wilson and Jenny’s friend Elaine are cornered in a parking garage by the pool room thugs Avery has hired to kill them. These are camera movements associated with subjective realization. Common to both directors, the function of these shots is narrative, showing us the moment at which a character realizes something pivotal by pivoting the camera itself.

Tracking shots are also used by both directors to evoke the feeling of being chased: the camera tracks Thornhill as he runs for shelter across the cornfield in North by Northwest for the same reason that it tracks the muzzle of Avery’s handgun during the final gun battle in The Limey.

Both films use “adjustment” shots — or shots in which the camera wobbles, zooms in or out quickly, essentially “adjusts” itself — to mimic the feeling of looking through photographic equipment. Thornhill fiddles with his 10¢ viewscope as he gazes at Mt. Rushmore. Wilson imagines the moment when the reconnaissance photos of Valentine were taken as he examines the photos in the head DEA agent’s office.

Pans are used to suggest the linear movement of trains and cars: Hitchcock uses back-to-back pans into and out of the Twentieth Century as it speeds to Chicago, Soderbergh uses back-to-back pans as the DEA agents stakeout Wilson and Elaine. In the first pan, the hit men exit the pool hall as Soderbergh pans across the parking lot to show a DEA agent in his car adjusting — or panning — his rearview mirror to catch them as they leave. In the second pan, Soderbergh puts the camera inside the agent’s car looking out over the dashboard. Elane’s Volvo pulls into view, then does a U-turn as the camera pans across to the side mirror, disorienting the viewer (and, presumably, the agent), as it seems the Volvo has continued moving straight ahead.

Also important are some moments when the camera does not move or appear to move, as when the camera dollies back from an object as the object moves forward, creating the effect of stillness even though both the character and the camera are moving. This is an uncanny effect, and it seems to occur when characters are less taken by their physical movement than by the inner workings of their own minds. Hitchcock uses it as Thornhill careens down a coastal highway in a drunken stupor.3

Soderbergh uses it as Wilson glides along the Pacific Coast Highway lost in memories of his former life in Britian. In Hitchcock’s shot we are made slightly aware of the movement by seeing the coast rush by through the rear windshield. In Soderbergh’s, the camera mounted high above the front of the car, we see the embankment reflected over the dashboard.

The camera also holds still for moments of violence, although in Hitchcock the violence is received — twice a punch is thrown into the camera, once by the Professor’s forest ranger, and once by Leonard — and in Soderbergh the violence is eschewed. As Wilson re-enters the warehouse to kill Valentine’s goons, the camera holds outside like a getaway car, the flashes of the gun’s discharge our only visual evidence as the shooting actually takes place. When Wilson exits, the camera rushes to meet him, bloody-faced, as he shouts to the sole survivor, “Tell him I’m coming! Tell him I’m fucking coming!” When Wilson throws Valentine’s hired muscle over the railing at the party, it takes place over Valentine’s shoulder, through a window, and out-of-focus.

But Soderbergh is careful to juxtapose this actual, “discreet” violence with violence that is imagined and far more “explicit,” as in a later scene where Wilson visualizes himself approaching Valentine three times over and firing at close range into three different locations. The obliqueness of the real violence and the explicitness of Wilson’s fantasies describe the character’s deep level of repression without any verbal mention of that repression.

Perhaps the most straightforward element to the discussion of camera movement is the distinction between Hitchcock’s placed, steady camera and Soderbergh’s more active, handheld camera. Jameson suggests in “Allegorizing Hitchcock” that a “placed” camera is filming while an “active” camera is “looking.” While it seems this is the case during points where the camera is obviously being moved — as in those points described above — this is not true in the case of tripod versus handheld camerawork. Instead, the difference serves to locate the film’s look-and-feel within a class structure: Soderbergh’s handheld camerawork has a distinctly “low-budget” and “unprofessional” feel that is appropriate to a character who does not show any signs of Hollywood slickness.

This “passive/active” relationship, as Jameson calls it, is also present during the shot-to-shot movement in the editing of the films. While Hitchcock may make many cuts during a single scene — the opening conversation of Vertigo has something like 62 — they are usually seamless and smooth, making it feel as if the film hasn’t been cut at all. One notices the long shots in a film like Rope, of course, but perhaps this is because Hitchcock has more control over a continuity of his own construction than over “actual” continuity. He rarely uses intercutting — the opening of Marnie is the only example I can recall — but, when he does use it, it is to great effect. The opening cuts of Marnie — silent, close, and broken by fragments of a totally different location in an office — are extremely evocative of Soderbergh’s editorial technique throughout The Limey. Soderbergh actively cuts the film, severing audio and visual tracks and making near-constant use of intercutting to suggest that things in Wilson’s world just won’t quite line up. Jameson suggests that Hitchcock’s editing is able to construct spatial experiences as a kind of language involving the close-up,4 long-shot, and bird’s-eye-view as virtual parts of speech,5 but Soderbergh takes this approach even further, masterfully chopping 32 bits of film together in one two-minute long sequence that is bounded by the simple action of opening a door and walking outside. In Soderbergh’s hands, the shots are not used simply as parts-of-speech, but there are actual overtones and inflections to these parts, as each time he revisits them we glean something new. The first minute of this incredible montage follows:

a door

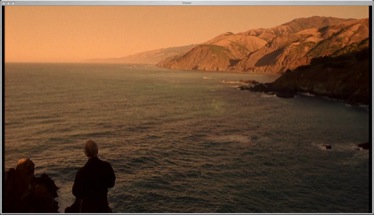

back of Wilson on a cliffside

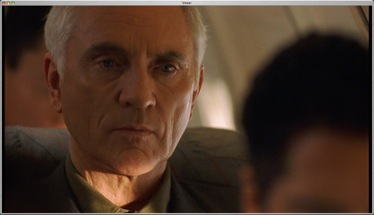

Wilson on a plane

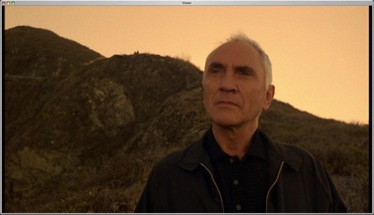

front of Wilson on a cliffside

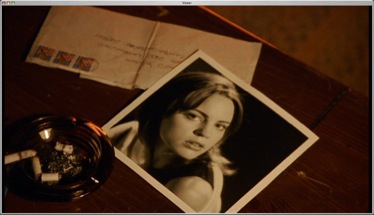

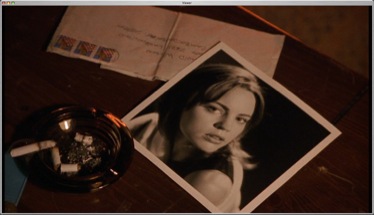

a picture of Jenny and an ash tray

Wilson in his hotel room smoking

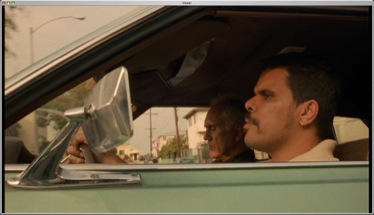

Wilson and Roel in Roel’s car talking about Jenny’s cremation

Wilson in his hotel room smoking

Wilson and Elane on a film set talking of Jenny’s love for the ocean

front of Wilson on a cliffside

old footage of Jenny at the beach

the film set

the door opening

Wilson’s hotel room

Wilson on a plane

a picture of Jenny and an ash tray

Wilson’s hotel room

So, as the door to the future opens, Wilson looks out over the ocean, is reminded of his distance from home, reminded of his daughter, now turned to ashes, and reminded of a life that’s now behind him. We see the characters of his current life — Ed Roel and Elaine, both on the car trip with him to Big Sur — and we see him trying to put the events of the past together with his present situation as he sits alone in his hotel room. As the door to the future opens, Wilson realizes it’s also the closed door of his repressed past, and his rage comes flooding back. This reaction determines the future, and the final minute of the montage affirms our fears:

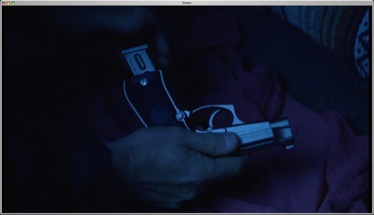

a gun

Wilson in his hotel room

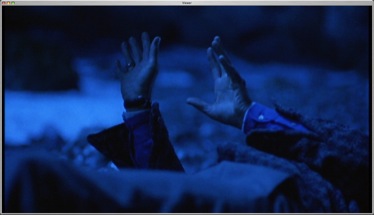

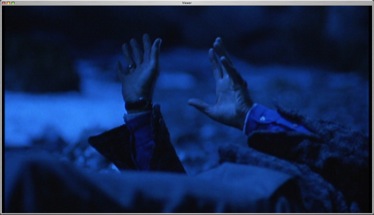

Valentine’s helpless hands on the ground

the gun

a house in Big Sur

the airplane

Valentine’s hands

the house

the door

Jenny’s picture

the airplane

the door closing

Here it is in one frightening minute: Wilson’s murder weapon, motive, premeditation, arrival, execution of Valentine, and his later escape from America. Soderbergh has shown us in one minute what will transpire for the next 25, all in the space of a door’s opening and closing, that in-between space, like the passing of one frame to the next.

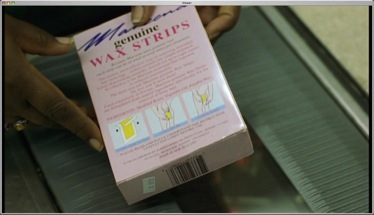

Each of the other characters in The Limey is introduced with the same kind of editorial economy: Roel’s Puerto Rican heritage comes in a divorced audio snippet: “Ed Roll?” “Eduardo Roel.” Valentine gets his own trailer — Soderbergh’s idea — of scenes that, as The Who music suggests, show “King Midas with a curse.” And Elaine is introduced by an uncut shot of her groceries passing one-by-one over a bar code scanner, naturally edited by their movement in and out of the shot.

While the inner lives of Hitchcock’s characters are not so deeply explored in North by Northwest, it seems that this is also not his particular interest, as nearly everyone in the film is hiding behind another identity to begin with: Thornhill/Kaplan, “Eve Kendall” Government Agent, the unnamed “Professor,” and the surname-only villain Van Damme. Instead, Hitchcock uses the film’s spaces themselves as characters, taking time to presence each one before heading into the scene, as he does, for example, during the scene in the cornfield, where rapid-fire edits serve to disorient us rather than to dispatch a great deal of “information”6 over a short period of time.

Ideological mobility and exchange

The ideology of these spaces, as Jameson wisely demonstrates in “Spatial Systems,” is inseparable from the spaces themselves, so, as “Allegorizing Hitchcock” dedicates itself to explaining, each of the scenic “characters” in Hitchcock’s film actualizes or reifies an ideal. “Spatial Systems” shows this process of allegorical transformation — “allegorization” — in North by Northwest. As Jameson walks the reader through some of the film’s crucial spaces

the “Townsend” Estate

the cornfield

the pine grove

the Mercedes in the car chase scene

Mt. Rushmore

Kaplan’s hotel room

he repositions each in relation to the others. The Estate is a vast amount of “owned” land, but the cornfield is even vaster. The cornfield is also a metaphor for nature, but it is much more barren than that of the enchanting pine grove. The Mercedes in the car chase scene nearly drives off the edge of a coastal highway, but this craggy cliff-side is little compared to the extreme edge of the “face” (note double meaning) of Mt. Rushmore. Mt. Rushmore is also a series of representations, but these are far more literal than that of Kaplan’s hotel room, which, as Jameson writes, “[is] a ‘form’ in the most rigorous sense of the word, so that Hitchcock’s ingenuity lies in giving representation to what is somehow, by definition, beyond it.”

Thus, a space’s mobility in Jameson’s system — like the spaces of the cornfield and Mt. Rushmore — is built around what the space itself lacks. The cornfield and Mt. Rushmore lack both an unquestioned naturalism and an unbarred entryway: it’s impossible to get oriented in the barren, semi-private, semi-public space of the cornfield; it’s impossible to climb safely atop the dynamite-blasted rock outcropping that is the largest representation of the most public men of American history.

The shared spaces of The Limey and North by Northwest also lack. The similar operation of the unnatural, inaccessible famous cliff side in both films is one we have already seen. In both films the coastal road lacks stability: Thornhill and Wilson grow more deeply entrenched in their situations after they drive on this road.

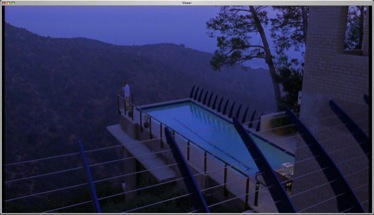

This destabilizing force is also found in the Modernist houses: Thornhill climbs precariously out to the edge of Van Damme’s Rushmore cabin while inside Eve is found out and Leonard hatches a plot against her; Wilson and Roel also venture out to the edge of Valentine’s patio, the far edge of which is unbanistered, as Wilson asks, “What are we standing on?” “Faith,” responds Roel. This is less than Wilson needs to ground him, and, after his fantasized execution of Valentine, he tries to gain a toe-hold in reality by tossing a bodyguard off the patio’s edge.

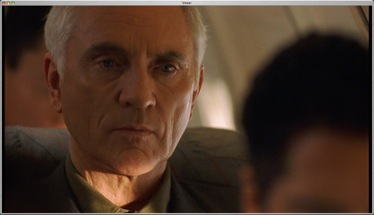

In both films the airplanes lack direction: the psychotic crop-duster in North by Northwest swoops, loops back, and turns around, meandering through the air while attempting to catch Thornhill on the ground; the prevalence of shots of Wilson on commercial airplane7 as light passes over his face8 make it impossible for us to recognize his as his flight to America or his “flight” — literally, an escape — back to Britain after killing Valentine.

Both hotel rooms are marked not by respite but by movement, Kaplan’s constantly leap-frogging around the country and Wilson’s positioned so close to the airport that a plane zooms low and large over his head as he finds the key to his room.

Finally, the total spaces of both films — Hitchcock’s America and Soderbergh’s L.A. — lack a humanizing population and a convincing realness that makes the characters of Thornhill and Wilson seem all the more alone and their situations all the more uncanny and desperate to us.

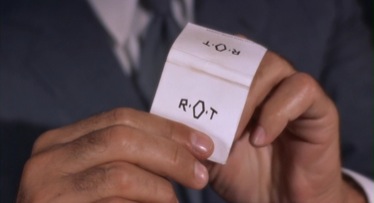

There are so many instances of things missing in North by Northwest that one can scarcely keep track of them all. One “empty chain” might include: Thornhill’s middle initial, “O,” which “stands for nothing,” he explains, reminding Eve on the Twentieth Century that his initials spell “ROT,” itself a kind of decay into nothingness, like the rotting corn in the cornfield to which he unwittingly travels, where a farmer explains that “they’re dusting crops where there ain’t no crops.” By the end of the film Thornhill, branded as the nonexistent Kaplan, is so enmeshed in a system of lack that he asks Van Damme to hand over Eve as the price for “[his] doing nothing,” all the while complicit in an elaborate trick with the Professor that involves a gun with no bullets.

Soderbergh presences lack in The Limey in more subtle ways. There is, of course, the editing, the separation of sound and image that is such a fundamental part of the film, and this technique is specific to scenes of trauma. When Wilson finds out about Jenny in the warehouse and when he and Elaine are nearly gunned down in the parking garage, Soderbergh strips the sound away. There is the intercutting of footage from Poor Cow, which now has a diminished relationship to the original, as it must “stand” for two things at once.

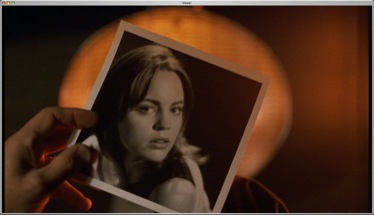

There are all the representations of “Jenny” that destabilize Wilson’s actual daughter and make her a “form” in the way that Jameson applies it to Kaplan’s hotel room: Soderbergh gives us memories of Jenny, a photograph of Jenny, and Adhara, Valentine’s new girlfriend who looks like Jenny.

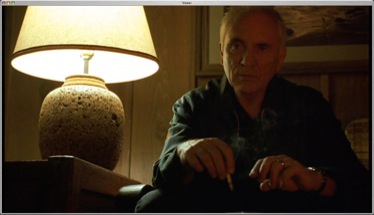

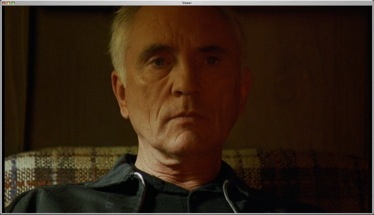

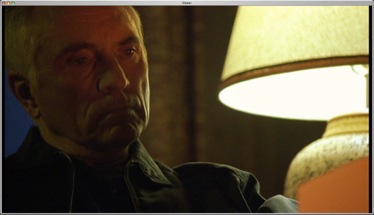

But perhaps the most striking lack comes in the simultaneous lack and overwhelming presence of the past for Wilson and Valentine. Wilson’s mind is constantly flitting back to the past, trying to rebuild a sense of himself after the loss of so many years of his life in prison and the loss of his beloved daughter. Valentine explains what he’s lost to Adhara, fresh-faced in the bath of his grandiose Modernist house, and it’s a past that he’s now not even sure existed. He says, “Have you ever dreamed about a place you never really recall being to? Someplace far away, only half-remembered when you wake up. When you were there, though, you knew the language. That was the ’60s. Not that, either. Just ’66 and early ’67. That’s all it was.”

Essentially, Hitchcock and Soderbergh strip their characters down to such an extent that either the character must embark on a quest in order to reconstruct his lost identity — this is the position of Thornhill and Wilson — or the character serves to represent an ideology — this is the position of the two villains, Valentine and Van Damme.9

However, in the case of the villains, these specific ideologies are somewhat murky. Van Damme’s European background and hatred of the U.S. government, hot on his trail during the Cold War, make his Marxist leanings a possibility, but he is also a monument to Capitalism, an importer/ exporter with hired hands who escort him from a fine arts auction in Chicago to his secluded estate near Mt. Rushmore where his private jet lies waiting to take him back to Europe with his precious microfilm. He seems, seen this way, to be the prototype of the international jet-setter.

Valentine is similarly in-between: while his dreamy ’60s aesthetic of “make love not war” should position him squarely in the leftist-Marxist camp, he is also a fat-cat record executive with one house in the Hollywood Hills, another in Big Sur, and enough cash left over to have all the bodyguards and vintage Santana posters he could ever wish for.

The protagonists’ politics are less muddied: Thornhill, an advertising man who’s tipping as often as he’s hopping into other people’s taxies, is an opportunist and a staunch Capitalist to boot: after being duped into working for the government, Thornhill wants nothing more than to return to his private life of things and comforts, including his marriage to Eve, also reclaimed from the government. Wilson, on the other hand, comes from a Socialist country and is interested — as he says twice — in “a different kind of satisfaction” than the kind that money can give him. In-and-out of jail since his youth, Wilson’s been lured by “the money,” as the DEA agent repeats over and over, far too many times. Instead, he’s after justice for his daughter and a prompt return to Britain.

Driven by what they lack, and fuelled by men who can offer them all that they wish to have, while embodying all that they despise, Thornhill and Wilson set out to make an exchange with these “dangerous men.” This exchange is foregrounded by both directors, so that all the peripheral exchanges that the protagonists must make in order to reach this final exchange become increasingly pointed. Exchange in North by Northwest is variously affiliated with Death, Art, and Love, particularly in the auction scene, where Thornhill says all of the following: “I’m practicing the art of survival…. I didn’t realize you’re an art collector, I thought you just collected corpses….” “[To Eve:] I bet you paid a pretty penny for this piece of sculpture. She’s worth every bit of it, I assure you. She puts her heart into her work. Her whole body, actually,” and, finally, as the police escort him out, “Handle me with care, I’m valuable property!” Twice there’s the equation of Death and Love as Thornhill and Eve woo one another: “Maybe you’re planning on murdering me tonight?” she asks him on the train, “Shall I?” he asks. “Please do,” she replies. Then, in her Chicago hotel room, he says, “Have you ever killed anyone? Because I bet you could tease a man to death without half trying.” And there’s the conflation of Death and Nature as the farmer tells Thornhill, “Some of them crop duster pilots get rich, if they live long enough.” In each of these many cases, dialogue maps an exchange of ideas between two polarized tropes.

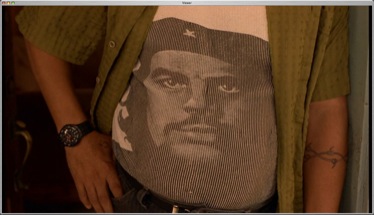

The notion of exchange pervades The Limey as well, but, unlike North by Northwest, which alludes to Marxism by erecting a backdrop of allegorical exchange against which the battle of Cold War politics and American private life might be waged, The Limey shows monetary exchanges and class disputes without an intermediary device. There is an undercurrent of class antagonism running throughout the entire film, screenwriter Lem Dobbs explains, “one of its major themes is this struggle, which is not second-hand to Americans; I think it would play better in England, where this sort of thing is more a part of their day-to-day lives” (DVD). Roel is always shown, for example, wearing a Marxist t-shirt, first a subtle vignette of Chairman Mao, then a dramatic tank top of Che Guevarra, looking so similar to Roel’s own face that Soderbergh’s tilt up from the gut-hugging shirt to the face of Wilson’s companion strikes one as particularly uncanny.

And Elaine, with her supermarket shampoo and movie-of-the-week acting parts, is no higher up on the social hierarchy. Several times Soderbergh shows his characters at the moment of a purchase: Wilson purchasing a gun, Elaine purchasing her groceries, and Avery purchasing the hit men. Or discussing money: Valentine’s muscle wait outside the Explorer and discuss a “sliding scale,” the hit men discuss the fairness of their take, Valentine wheels and deals at his party, and Wilson and Roel discuss tipping the valets.

The most crucial monetary discussion, however, takes place between Wilson and the head DEA agent, where both men discuss money as a false solution to their problems. Wilson begins the dialogue, using feudal terminology to impress upon the DEA agent his respect for him. “Look, squire,” he begins, “I’m in your manor now.” He says that the “slave Valentine” doesn’t share his respect, nor does he know how to “bide [his] time.” “Bide your time,” Wilson repeats three times, as if time is what comes at the highest price. And perhaps it does: after all, it is the loss of time with his daughter and the lessening time in his own life that compels Wilson to act. “Money isn’t what lights your fire?” the DEA agent asks, alluding to the agents burning heroin outside his window, still unseen. “In the past, granted, I have been known to redistribute wealth,” Wilson says, sounding like a modern-day Robin Hood (or Karl Marx, for that matter), “but I’m after a different kind of satisfaction.” This satisfaction — which Wilson describes to Elaine during their evening together — comes with justice being done. And, with this justice, comes an affirmation of Wilson’s own life, in the lower classes, yes, but his hands are unstained by the “damned spot” of ill-gotten wealth.10 This, warns the DEA agent, is a slippery slope: “The hardest thing to move is the money — the money — the money — because you can move the drugs but what you can’t move is the money. Usually you’ll find some rich fool to bank the cash, make it look legit. A rich fool in danger of overextending himself, too worried about not being rich anymore.” It is the fear of losing an attained class status — a fear that comes with the problem of maintaining wealth, a fear that, if realized, would mean a long journey down the social ladder from super-consumer to common producer — it is this fear that drives the “dangerous men” in both films to do terrible, terrible things.

-

They were also supposed to have shared the episode of an auction: Wilson, Stamp’s character, was to buy his gun at a gun auction, but the lack of gun shows in L.A. proved prohibitive. Instead, the scene was moved to a school playground (DVD). ↩

-

Note that in one his crossing is against an obstacle parallel to our view and in the other to one perpendicular. ↩

-

Note that there is a drunken-driving scene in The Limey as well, during the fictional account of Jenny’s death as she speeds drunken down the hilly road from Valentine’s pad. Soderbergh adopts Hitchcock’s head-on car-mount here, to remarkable effect. ↩

-

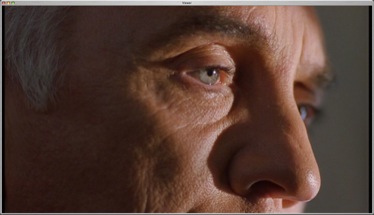

Jameson’s discussion of the close-up in “Allegorizing Hitchcock” is interesting to note here, particularly in relation to Soderbergh’s explicit strategy of including close-ups of Wilson to “show him thinking and working things out” (DVD). Jameson, instead, suggests that the Hitchcockian close-up “[emphasizes] the structural externality of the camera, the fact that a ‘face’ can finally never tell us anything we want to know, nor can it even ‘confirm’ what we have learned of a certainty from some other source. The close-up, in other words, tends by its own logic to strengthen an uncertainty the plot itself may have already attempted to dissolve.” ↩

-

As Jameson writes in “Allegorizing Hitchcock,” “[A] gap confronts the analysis of film… the problem of what to do with the individual frame (or, somewhat differently, the individual shot). Are these the words or the sentences of ‘filmic discourse’? ↩

-

The idea of cinematic “information” is an interesting one to ponder. Hitchcock was certainly interested in “filmic knowledge” as Jameson calls it, and so is Soderbergh. He is not the “informing power,” however, that auteurists would have us believe Hitchcock was; instead, Soderbergh says that he is interested in “new ways of giving the audience information” (DVD). This cinematic “information” is “given,” in Soderbergh’s formation, not “imparted” or “told.” This is in keeping with a de-emphasis of the filmmaker and a re-emphasis on the narrative’s form, which, in the case of Soderbergh, is that of “non-linear storytelling” (DVD). ↩

-

Note that the “Northwest” of North by Northwest is actually Northwest Airlines. ↩

-

The image of light passing over a face — used twice in The Limey — is a particularly beautiful one, and recalls an image of Christian Metz’s found in Jameson’s “Allegorizing Hitchcock”: “the spectator is the searchlight…, duplicating the projector, which itself duplicates the camera, and he is also the sensitive surface duplicating the screen, which itself duplicates the film-strip.” Jameson goes on to say that “what Metz characterizes as the screen versus the searchlight… is also easily identifiable as Abrams’s romantic ‘mirror’ and ‘lamp.’” Of course, the light on Jenny’s face in Wilson’s memories is made by a mirror reflecting the lamp of the sun, and her face, so illuminated, is then recorded by the film in the camera, on which light leaves an indexical and unforgettable mark. Not only does this device serve to link Wilson on the plane to Jenny on the beach, but it also suggests the kind of spectatorially simultaneous reflection/projection that is just how the cinema itself behaves. The idea that one’s mind might behave like a movie is a powerful and interesting one to say the least. ↩

-

V, the Villains’ shared initial, has a host of suggestive possibilities. V stands for vector, or a movement through space, but it’s also the notation for a forking path or a nodal point. There is also the connection with rocketry, such as the V-1 and V-2, suggestive of the Cold War specifically and of destructive trajectories in general. I might also note here that two characters in North by Northwest share the initial K — Kaplan and Kendall — interesting because both are characters fabricated by the State. Of course Kafka’s Joseph K. comes to mind here, as he is also a man deprived of his identity by the state. K also stands for king in chess, the pivotal piece who moves constantly and must be protected. The letter itself was introduced into the English language with the word “knife,” a weapon seemingly used by “Kaplan” (though in fact used by Van Damme’s devious gardener) when Townsend is killed at the U.N. Building. K stands for karat, a way of measuring worth, and in math it is an oblique vector on the Z-Axis, much like those oblique vectors that begin Saul Bass’ titles for North by Northwest. A K2 is a rock face and the second-tallest mountain in the world, and, finally, K begins many words concerning movement like kinescope, kinetic energy, kinesthesia, and the famous Kino-Eye. ↩

-

Hands are an important image in both films, serving as a kind of determining device for a person’s moral character. In Hitchcock’s film, there are the gloved hands of the gardener when the real Mr. Townsend is stabbed; Thornhill’s hands several times over, especially when embracing Eve; Van Damme’s hands on Eve’s neck at the auction; and Leonard’s gloved hands during the chase on Mt. Rushmore. The covering or uncovering of the hands here seems to be related to a person’s guilt or innocence, as Thornhill’s hands are seen plainly to be unmarked, meaning he simply cannot be a killer. In Soderbergh’s film, the image of outstretched hands on the ground is one of submission and defeat. The actual shot of Valentine’s hands on the beach is used several times, and twice Avery is taken down and begs for his life. One gets the sense that Wilson, however, is on a crash course, and that, should he be placed in the same situation as these men, he’d rather die than be alive and a coward. Pride goes before Wilson’s fall. ↩