Out of Phase and High On Fruice (with David Reinfurt)

David Reinfurt, a coauthor of the sci-fi novel PHILIP, and I are sitting at Cakeshop, a bakery / concert hall / record store on Ludow Street in New York’s Lower East Side. We sit at separate but neighboring tables, our computers open and facing each other. Our interview will be conducted without exchanging any words, almost like telepathy, or possibly just a lazy afternoon of instant messaging. Behind us a rock band is having publicity photos taken. Math rock blares as I snag the coffees.

Rob: How did the idea for PHILIP come up, and how did you decide to organize the work?

David: It was a remnant of Manifesta 6. PHILIP was originally conceived as a science fiction writing workshop by Heman Chong, an artist who was participating in Manifesta. His project there was to convene a science fiction workshop as a way to both explore a genre but also to actually make a story together. So from the beginning it was focused on making a book. When Manifesta 6 was cancelled, then Heman wanted to conitinue the project. One of the curators, Mai Abu ElDahab found a place where it was possible: Project Arts Centre in Dublin.

I put on headphones to concentrate as David takes a moment to think.

David: I’m typing quite slowly—must be the proximity. In Dublin Mai proposed to take the budget…

Rob: How did Mai’s work as a curator function?

David: I just predicted your question! HOW’S THAT FOR SCIENCE?

Rob: AMAZING. You’re a mind reader. PHILIP would be proud.

David: He would attribute it to Precognition.

Rob: Go on…

David: Mai took the regular exhibition budget and setup for a typical exhibition, and she rechanneled it into this workshop format. This made a certain sense as Project Arts Centre typically mixes exhibition with performances, including an ambitious theatre and music program. Mai’s role then was then to keep everything on track when we were trying to write and make the book.

Rob: How did you function day-to-day? I saw that you were in a bar—it almost reminded me of a Hollywood writers’ room. Did you bring in preconceived ideas?

David: Nope. But Heman Chong and Leif Magne Tangen, who organized the workshop, brought ideas in. Only in terms of a frame, though—the book would be called PHILIP, it would be set in PHILIPVILLE, and it would roughly sketch out an apocolypse of sorts. (If there can be an “apocolypse-of-sorts,” it’s really all or nothing, I suppose.)

Rob: So you broke things up by chapter? Or everyone was contributing a certain number of pages?

David: No, actually much more fluid. On the first day, we were each asked to write a beginning for the story: a setting and beginnings of characters. Then we all read ours to each other. This was only to make some assumptions begin to be common amongst us. After another day, it became increasingly clear what each of our strengths might be, and we began to write to them. So it was as if we were each writing autonomous pieces, and the the groupwork was to sketch out a plot to connect them. It was all pretty nicely backwards. The way the pieces fit together was surpisingly organic and forced at the same time, meaning that we were each following our own courses and gleefully amending our efforts also for the sake of the whole. The eventual result is a quilt, but quite cleanly connected.

Here is a drawing of the plot. On the wall behind us with cosmin (in pink) gesturing towards it.

Here are all the players. It’s a motley crew to be certain.

Rob: We share a love of group photos. Let me circle back for a second, though, to your interest in sci-fi. In the Frieze review of PHILIP, Aaron Schuster concludes by saying, “A modest prediction: The time for sci-fi in contemporary art has arrived. We will soon see more shows organized around this ‘minor’ genre, with Philip K. Dick figuring as an essential reference. In other words, look for more future in the near future.” What kinds of opportunities does sci-fi present to you as a genre or framework?

David: Well, speculation first and foremost…

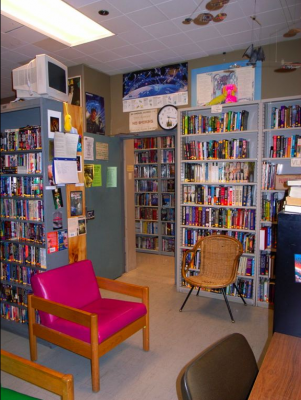

Hey Rob, look at this—it’s the MIT Science Fiction Society Library.

Rob: I’ve got a collection of reading room photos going too! I don’t have this one yet, though—good find. You had what appeared to be a sci-fi library / reading room at the opening. How did that develop?

David: In Dublin there was a vitrine in the bookstore, all sealed up with many sci-fi titles. and then at the opening in New York there were several things that connected back: there were the PHILIP books themselves, but also there was a guest, Larissa Harris, who sat quietly in the corner and read a Stanislaw Lem story on constant repeat to whomever would pay attention. We also had a hairdryer we found on Ludlow Street that day. (Funny, how simple it is to make something seem like it’s from the Future.)

Rob: You’re right. Domes are almost always from the future. Especially clear plastic domes.

We take a quick break. More coffee.

Rob: As you know I’m really interested in the Independent Group. Some of their activities, like the This Is Tomorrow exhibit, were really forward-looking, almost futuristic. Do you see a relationship between this kind of Futurism and sci-fi?

David: Absolutely, the Independent Group was all tied up with design, partly from an outside position. And design is all tied up with the future, since design is a usually a speculative proposition. Therefore, by the transitive property, the Independent Group is dealing with science fiction. Sometimes it’s in their iconography—like Richard Hamilton’s robot—though that it is really pop, and not sci-fi. The sci-fi comes through more strongly in things like the Parallel of Life and Art exhibition at the ICA in London, which featured images from science transposed to a gallery context. (Things that are the cutting edge of today look indistinguishable from fiction, of course) I’m not enamored with “sci-fi” as a rubric, though, and probably prefer Futurism, as you say above.

Rob: Was Philip K. Dick valuable you as a touchstone?

David: Well, kind of—and also not really. With sci-fi, I prefer a much drier variety, like the Strugatsky Brothers. Or simpler, like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. But it’s hard not to enjoy Philip K. Dick when reading him, I suppose.

Rob: I am an H.G. Wells fan myself. The classics. You could almost position Leonardo Da Vinci as a sci-fi writer, in that sense.

David: Certainly.

Rob: There do seem to be certain “Dickian” techniques, though, like the use of psudeonyms. Dick of course used Horselover Fat as a psuedonym for himself in VALIS, and I know you are a fan of Ben Franklin’s alter-ego, Richard Saunders, a.k.a. “Poor Richard.” It seemed in the wall plans I saw of PHILIP that there were certain obvious pseudonyms, like “Dexter” for you, or “The Bassist” for Steve Rushton…

David: I vetoed the Dexter name, but for sure the use of pseudonyms came part from Dick, but also at least as much from just being simpleton writers. Many of the other names are fairly arbitrary.

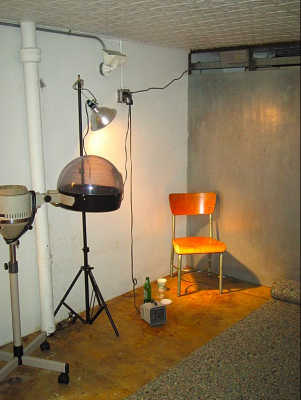

Rob: Let’s talk about the cover for a second—what’s the photo on the front cover?

David: Well, it relates to the hairdryer we were just discussing. A minute ago I said it’s funny how simple it is to make something seem like it’s from the Future. The cover image is of the person who served us all coffee everyday. In her non-coffee career, she is also a hairstylist, and she had an amazing up-do. So we thought she would make a good cover—we asked her and she posed just outside the room where we were working against a conveniently distressed wall. Here’s a picture of a picture.

Rob: It almost looked like one of those NASA photos of star nebulae or something, if you squint your eyes at it.

David: True, true. She only happpened to be wearing the leopard-skin jacket, a nice touch. She was fashion-forward.

Rob: She looks like someone who drinks a lot of FRUICE.

David: By the gallon.

Rob: I see the Lissajous curve on the back, could you talk about why that’s important to you?

David: The curve on the back relates to the front: the hairstylist’s hair looks like a Lissajous. I guess I had a running fascination with this figure. It’s the picture on an oscilloscope face of two simple electric signals (as sine waves) coming in and out of phase. I had an inkling that this figure might be a useful diagram to consider for the shape of the plot-line. A bunch of individual characters and writers coming into and out of sync.

Rob: Circling back as you said, the future connecting to the past…

David: …present as future, future as present.

David sends me a video of a Lissajous curve from YouTube. Then he pastes the following quote:

Easily mistaken for the infinity sign, the Lissajous figure is a horizontal figure-eight named after French physicist and mathematician Jules Antoine Lissajous (1822-1880). The shape is drawn by plotting a two-variable parametric equation as it calculates and recalculates itself over time. The resulting figure is the picture of two systems falling into and out of phase. Rob: Speaking of falling in and out of phase—isn’t it interesting how IM makes it hard to ride the natural rhythm of conversation?

David: Does. In. Deed. Which. Is. Why I. Like. Typing in. Short bits.

David’s phone rings. He leaves to take the call for a moment, then returns. He uploads an image.

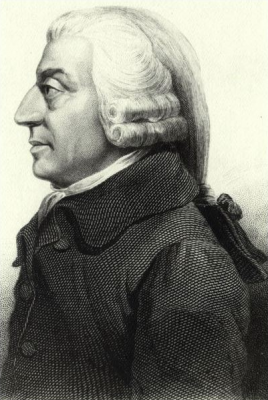

**Rob: That’s Adam Smith. “Time is money,” right? Or maybe you are typing with your “invisible hand.” **

David: The future is almost with us! We’re running out of time. I sense an apocolypse…

Rob: Okay, okay. PHILIP’s price tag is steep, € 85.70. In your article The Price of PHILIP, you wrote, “The novel’s price can be a signal, communicating expectations for its reception, commanding the reader’s attention and focusing the first reading.” The cost of the book is much more than a mass-market paperback, but not so much more than a nice pair of pants. It is much less than the average artwork, or even the average art multiple. This seems like fiscal territory that is rather accomodating to the spirit of the project.

David: It is certainly an in-between price zone. And that was immediately interesting, as maybe a reader doesn’t know quite where to place it. Prices are signals. They are not only a result of Mr. Smith’s “invisible hand.”

Rob: I know the pricing of PHILIP was conceived to cover the cost of the labor of creating the book. It’s interesting because Adam Smith contrasts labor with leisure, and of course the rise of leisure is tied to the rise of the novel as a form…

David: That’s quite interesting—the parallel to the rise of leisure, the novel etc. I hadn’t made that connection, but it fits perfectly, post facto.

Rob: Novels developed because rich people had time to read them.

David: Rich people have a spare € 85.70 too.

Strobe lights from the photo shoot behind us begin to flash.

Rob: Wow. So futuristic.

David: Really nice strobe lights—operating on my subconscious I imagine. Back to Mr. Smith: it is quite interesting how the “invisible hand” is his pop-culture legacy, because the work he was more fully involved in was an examination of the “political economy” of production. I love that term.

Rob: “Invisible hand”?

David: No, “political economy.” Anyway, the point is that Smith was more engaged in looking at the relationships and conditions that surround production, not just how laissez fair practices guide the economy.

Rob: So did the 1st edition entirely cover costs when it sold out? Are the 2nd and 3rd editions all profit? Is the current price, US$ 17.73, simply the cost to print from Lulu.com? So it covers the costs associated with that edition, not the production of the edition’s content?

David: In theory the 1st edition would have covered the costs, but in practice it didn’t. There were a number of mitigating factors. First, much of the 1st edition was given away to the writers—if we had sold them all directly it would have covered the project costs. So the 2nd edition price is derived by the total number of PHILIP books existing divided by the total costs. But it was always our aim to have the “profits” fund new editions. A way of working backwards into a mass paperback, though I don’t think it will be a mass paperback any time soon.

Rob: One of the most interesting things I read in THE PRICE OF PHILIP was what you had to say about the Network Effect as it relates to a novel. The classic example of the Network Effect is a telephone service. Someone who buys a telephone indirectly benefits everyone else who owns a telephone because they broaden the network and make telephones more useful in reaching people wherever they are. You write, “As additional copies of PHILIP are produced, the Immaterial Labor [definied as shaping cultural and artistic tastes as well as public opinions] of the workshop then is further dispersed over the additional copies—circulating and connecting places and people remote from its site of production, creating a network of readers and a sustainable economy in the process.”

David: Well, I love how the Network Effect is another name for the Economy of Scope. I love “Economy of Scope” as a phrase also. Very futuristic, I think.

Rob: Yes, and forward-thinking in the most hopeful way. Toward producing not lots of things, but things that matter lots.

David: I mean, books inevitably work that way—Oprah’s Book Club anyone? Read the same as me and we can have something to talk about. (I can’t believe I’m talking about Oprah.)

Rob: You always end up talking about Oprah!

David: What will she do in the future? The future is such an interesting thing to think about. I think the most important part of the exercise of doing PHILIP may be forcing thinking about the future along time scales that differ from those we generally view the world with. For example, I love the work of Stewart Brand and his long-thinking exercises like The Long Now Foundation, Long Bets and Scenario Planning. Simply put, these different efforts are simply part of an ongoing exercise to plan for longer time scales. So instead of a budget and plan for one year the same exercise is carried out for 50 year time frame. The maybe-suprising result is that the decisions are radically different and more inclusive of all types of factors. It’s a way to counteract the instant gratifcation of a market-based approach.

Rob: Is Brand’s Scenario Planning part of what’s going on with the current class you are teaching at RISD on electricity?

David: Exactly. I’ll just paste in the assignment here which may be useful:

PROVIDENCE, 22 FEBRURY 2038 — Nikola Tesla’s dream of universal wireless electricity has been realized, wrapping the world in a giant electric blanket. Always-on, transmitting instant presence from one place to another and powering increasingly powerful electrical and electronic apparatus, extensions of a global body in the ultimate Cybernetic system. And still, The National Grid electric company persists (in Providence, at least); they still measure what you use, tally your consumption and send you a bill. In light of these substantial developments, please redesign this electricity bill from 30 years in the future. The nicest part of the exercise is that by transposing a simple assignment to a farther out future, then conventions and assumptions become much more easily revealed. So it’s been quite a useful strategy. I want to keep on doing it in the future. Last Saturday, we had a walking tour of downtown Providence with the students where we met at 9.00 AM, and I told them as we got started that it was 19 April 2038 at 9.00 AM. Then we opened our eyes and surveyed the world 30 years in the future. It was temporary time travel though, I had a train to catch at noon.

Rob: As with PHILIP, you showed some short films as part of the class, right?

David: Yes, in both cases the fluid quality of a film and its well-documented conventions for adjusting time make it particularly nice.

Rob: So film is the ultimate time-travel device.

David: Cut, jump cut, wipe, and repeat. Should we start again?

This article originally appeared in Task Newsletter #2. If you like this little preview, go buy a copy and support this fantastic magazine.