A Workshop with Lewis Hyde

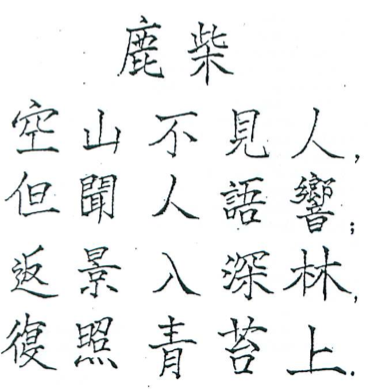

Above: A poem by Wang Wei (c. 700-761). The title has been translated as “Deer Park.”

Self-discovery

Yesterday I had the distinct pleasure of taking a writing workshop with one of my heroes, Prof. Lewis Hyde. Hyde has an excellent show up right now at the Japan Society called “Oxherding,” and the workshop was presented in connection with that show. The show notes describe the project:

The product of a collaborative meditation by two internationally known artistic visionaries, Max Gimblett and Lewis Hyde, oxherding is based on the Song-Dynasty Chinese “Oxherding Series,” a Zen Buddhist parable of self-discovery comprised of pictures and verse. A contemporary American set of perspectives on this greatly venerated Buddhist text, the exhibition includes six collaborative artist books, a series of 10 sumi ink paintings by Max Gimblett, and 10 poems in Chinese and three English versions translated by Lewis Hyde.

Hyde has shared his translations on his own website here. He explains the process of translating the poems using methods of varying length and correspondence to the original:

Each Oxherding text will appear in three different English versions: a “one word ox” which sticks slavishly to the Chinese (one word per character), a “spare sense ox,” which puts each Chinese syntactic unit into a simple English sentence, and an “American ox” (or “fat American ox”) which takes considerable liberties while trying to be faithful to my intuitions about the meaning of the series.

Though we had not been told in advance about the nature of the workshop, after seeing the show I guessed it would focus on the nuances and challenges of translation, and indeed it did.

Translating English to English

Hyde began the workshop by explaining that his work as a translator had had a very positive influence on his own writing, because of the difficulty we all have in rewriting or rephrasing our own words once we’ve written them. Often, in revising our writing, we make only minor changes or adjustments, rather than more meaningful and substantive edits to the text we’re seeking to improve. Yet revision is essential to successful writing: Hyde quoted a colleague who’s quipped that the revising is “a process that takes a text from egotism to altruism.” That is, with revision a text goes from its author’s own individual point of view to a place where it can be shared and where it will find resonance with a broader readership.

Our objective for the workshop was to adapt translation for our use in editing and revision. Instead of editing a text, Hyde challenged us to think about translating our English words into better English. He called this “translating English to English.”

Obama’s rug

Above: A new rug for the Oval Office, installed earlier this year.

After Hyde’s introduction, we started by looking at a few examples of this English-to-English translation in action. One of the examples was pulled from recent events. A few weeks ago, President Obama had a new rug designed and installed in the Oval Office, and it includes a number of quotations that he’s quite fond of, including one from President Lincoln (his famous “of the people, by the people, for the people” quote from 1863) and another from Martin Luther King, Jr. that King often said in his lifetime:

The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.

It turns out both of these famous quotes are in fact themselves quotations, or revisions, or adaptations, or English-to-English translations of sermons by the reformist minister Theodore Parker (1810–1860). In the case of King’s quote above, here is Parker’s original statement from a sermon in 1853:

I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.

Hyde joked that it’s as if midway through this thought Parker starts trying to actually calculate the measurement of the moral universe’s arc rather than focusing on the thrust of the phrase, which is where that arc takes us.

Ways of looking at Wang Wei

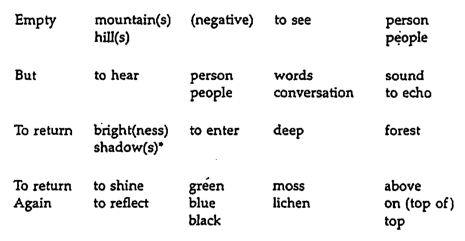

Above: A character-by-character translation of Wang Wei’s poem “Deer Park,” which is shown in its original Chinese at the start of this post.

We then turned to the first of our two writing exercises. Hyde is not a Chinese speaker, so he worked with a scholar at Harvard to prepare all possible English word translations for each character of the Oxherding text in a one-to-one matrix. He credited Eliot Weinberger’s book Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei: How a Chinese Poem Is Translated in introducing him to this approach. Weinberger’s book examines nineteen translations of a single poem by Wang Wei (c. 700-761), a wealthy Buddhist painter and calligrapher. The titular poem is “Deer Park,” and the book moves from looking at the characters to looking at a transliteration (Chinese pronunciation written phonetically in English) to the character-by-character translation and concludes with a translation by poet Gary Snyder from 1978.

Here’s a rather basic version from earlier in the book:

Empty mountain: no man is seen,

But voices of men are heard.

Sun’s reflection reaches into the woods

And shines upon the green moss.

His assignment to us was to “make four lines, or for sentences, or four syntactic units based on these indications of the Chinese original.” That is, using the matrix and this basic version of the poem, translate the poem from a clunky to a more elegant English.

The poem itself raises a number of questions. What does it mean? Who, if anyone, is its subject? The Chinese characters don’t assign for the same kind of subjectivity that the English language does, nor do they provide a distinction between singular and plural. The poem is classically Buddhist in its philosophy, and Hyde described a colleague who wondered if “the mind-states of Buddhism can even be accurately captured in English.” So the challenge of translating “Deer Park” is a vexing one.

Nevertheless, I gave it a shot and produced two attempts. As we read the basic translation together in class and discussed it, Hyde emphasized the word “empty” as being critical to the understanding of the poem. The mountain was empty, yet there was a presence of some kind, both in voice and in light from above. Putting the word first made me kind of read past it, and I wanted to give it more emphasis:

The mountains are empty. No one is seen

but some are heard.

Light returns to the forest,

reflecting the colorful mosses in the trees.

So “empty” now has more presence, so to speak. “No one” / “some” seems, in a way, more disembodied than “no man.” The matrix includes the idea of light “returning,” but it was not in our basic translation, and I wanted to reintroduce it as I liked its cyclical implications. Instead of choosing a single color option for the moss (green, blue, black), I opted for “colorful,” and left the reader to picture it for themselves. Finally, while the basic translation and others from Weinberger’s book have the moss on the ground, I always pictured it in the trees, accentuating the wind as it did when I visited Savannah, Georgia many years ago. A Japanese speaker in our class also guessed that the moss was in the trees, and Gary Snyder’s version includes this reading as well.

I had a bit of time to continue working on the poem, so I attempted another draft that pushed it a bit further and took some bigger risks:

The mountains, the hills: all empty, with no one in sight.

Yet voices can be heard in the distance.

At the close of day, the forest is filled again with sunlight,

shining through the blue-green mosses in the trees.

You could go on and on, it’s a wonderful poem that just keeps unfolding as you go.

Orwellian shepherds

For the second exercise, we turned to translating English-to-English in terms of tone. Hyde began by sharing this example from George Orwell’s famous essay, “Politics and the English Language.” Here is a Bible verse from Ecclesiastes:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

And here is Orwell’s “modern English” translation of the same verse:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

Our assignment was to “translate the 23rd Psalm into Orwell’s modern English.” As a refresher, here is part of the 23rd Psalm:

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures; he leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul… Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

And here is my attempt at the translation:

Guidance is essential to the reduction of anxiety. Leadership, too, has been shown to relax and restore subjects to a more focused and productive state. Even in late adulthood, or in convalescence, hospice, and other situations, subjects whose lives have been touched by strong guidance and leadership have noted a positive — even comforting — effect.

Depressing and eye-opening all at the same time. But a thoroughly challenging exercise to be sure. My fellow workshop members handled it in a dazzlingly wide range of ways, all of which were great, and we all felt we learned a lot. Hyde’s new book, which I’m thoroughly enjoying and definitely recommend, is called Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership — do check it out.