Tense Relations

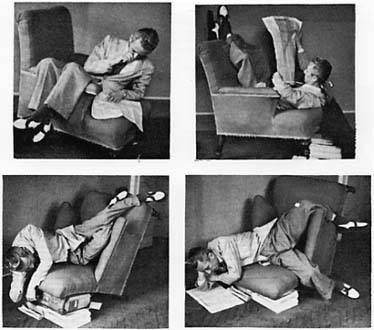

Above: Seeking comfort in an uncomfortable chair, Bruno Munari (ca.1950). From Air Made Visible (2000).

“It’ll never be known how this has to be told, in the first person or the second, using the third person plural or continually inventing modes that will serve for nothing. If one might say: I will see the moon rose, or: we hurt me at the back of my eyes, and especially: you the blond woman was the clouds that race before my your his yours their faces. What the hell…. I have to write. One of us has to write, if this is going to get told.” —Julio Cortázar, “Blow-up”

The Seated Reader

Designers have always been interested in chairs, but they have not necessarily always been interested in design essays. Like some essays, some chairs are made for specific positions (like lounge chairs), and others are made for specific places, whether they’re general places (like side chairs), or specific places (like office chairs). Some designers might like chairs for partly this reason. The designers of chairs are able to represent to us the different positions their creations put us into. But the critical positions essays put us into are, mysteriously or not, less comfortable for us to think about.

But perhaps the two things are related by more than metaphor. Before I begin reading an essay by someone, I ask myself, “How should I be sitting? Is this a “sit back” bit of reading, or a situation where I should “lean forward”? Was the writer sitting in the same way? What was the writer’s position? Maybe it’s not such a critical question, but I ask it anyway because it gives me a chance to embody the writer for a minute, to sort of position myself as the writer is positioned so we’re starting out from the same spot together. In this case, dear reader, I’m sitting back.

I picked up a favorite book of mine the other day, Gerhard Richter’s The Daily Practice of Painting, a book I bought because I liked the name. Many would agree with Richter when he notes that being a creator is a constant effort that is never perfected. It is something to be practiced daily. I already think about my design work that way, but lately I have started to think about my writing that way, too. In preparing to write this I read a conversation between Michael Rock and Rick Poynor from a few years ago titled “What is this thing called graphic design criticism?” (available in 2x4’s “Reading Room”) and Poynor says emphatically that “The critic can only learn what is possible by constantly writing.” Yes, so it seems. A critic who ceases to write is like an actor who ceases to perform: these are mere civilians.

The Artist, The Critic, The Journalist, The Actor

Much of the effort expended by creative people is no different from a shopkeeper’s. They take inventory. Many objects from visiting merchants and printed catalogs vie for the shopkeeper’s attention, and the shopkeeper must determine what’s to be done with them and whether they should be put up for sale within the limited space of the shop. Taking inventory requires judgment, and this judgment is constant and laborious. One of the first observations Richter makes, in 1962, is that “There is no excuse whatever for uncritically accepting what one takes over from others. […] This fact means that there is nothing guaranteed about conventions; it gives us the daily responsibility of distinguishing good from bad.” Here, his tone is a critic’s. He issues an emphatic directive to an audience, and then, assuming they agree, draws an inference from it. Four years later, Richter’s notes are more self-defining: “I pursue no objectives, no system, no tendency; I have no program, no style, no direction. […] I steer clear of definitions. I don’t know what I want. I am inconsistent, non-committal, passive; I like the indefinite, the boundless; I like continual uncertainty.” These words are not a critic’s. They are an artist’s.

When artists write as makers, they tend to write in the first person. When critics write as observers, they tend to write in the third person. If critics use the first person, then it is plural and its viewpoint belongs to the audience. Artists may be wildly contradictory in their arguments, as Richter is, in order to obscure or complicate their ability to speak authoritatively for their works since, as artists, their responsibility is to create works that more or less speak for themselves. Critics do not have this luxury. In order to adapt to changing times, the critic must inevitably revisit his positions, but a wildly contradictory critic will quickly render himself pointless.

There are also journalists. Journalists are observers, but they are not critics. Like critics, they must be clear, but, unlike critics, they should not offer the reader judgments: just facts. These facts may arrive in a highly stylized way, as the New Journalists understood, but if they cease to be facts then the writer, in the most classic sense, ceases to be a journalist and must be playing some other role.

Finally, there are people who routinely play other roles, and they are called actors. Like artists, actors use the first person as their primary tense, embodying the writer’s characters (via the director) and performing them for the audience. The actor is commissioned by the producer to play a specific role in the production. The actor has a task, which is to create his character. In creating a character, the actor’s own opinions must be deliberately ambiguous and non-judgmental. The actor’s character is just one element of the story. Actors are often quick to note that when they judge their characters’ actions preemptively, they somehow fail to relay the essential facts of their character to the audience. Actors must withhold judgment. Because of an actor’s commitment to reporting emotional facts directly, they are a bit like journalists.

Here’s a journalist (Larissa MacFarquhar) writing in The New Yorker about the experience of an artist (John Ashbery) responding to criticism:

He would prefer to read poems only for himself. He dislikes writing poetry criticism. The evaluating impulse is totally foreign to him. He has no interest in developing a set of criteria by which he might decide whether a poem is good or bad or great […] It’s simply that, for him, poems are pleasurable tools. He wants a poem to do something to him, to spark a thought or, even better, a verse of his own; he has no urge to do something to the poem.

The artist uses art to generate. The critic uses art to evaluate. The journalist uses art to explain. The actor uses art to empathize.

The Hybrid, The Schizophrenic

Michael Rock makes this complex set of relationships clear early in his conversation with Rick Poynor. He observes, “Design work is exchanged intra-professionally, through publishing, lectures, promotional material, other written forms. Publication may lead to speaking engagements, workshops, teaching invitations and competition panels – all of which in turn further promote certain aesthetic positions. At the same time, a historical canon is perpetually generated, a canon that will influence the next generation of designers by indicating what work is of value, what is worth saving, what is excluded.” So future designers will generate work based on other work they’ve seen, design critics will assign value judgments to the work being published, and journalists will publish and cover more of it for everyone to continue talking about.

But how journalists will cover it is another matter. While Poynor acknowledges that one of the pitfalls of practicing “ordinary journalism” in a design context is that this kind of writing “fails to make its critical positions sufficiently explicit,” he also laments the fact that “a more academic form of criticism to compare with those generated by, for instance, art, literature, and cultural studies […] will have limited appeal to professional readers,” or readers who function solely as practicing designers. To remedy this, Poynor suggests increasing the contributions in the popular professional press of a hybrid journalist/critic who practices “critical journalism,” meaning

the kind of writing you find on the arts pages of the Sunday papers: informed, thoughtful, skeptical, literate, prepared to take up a position and argue a case, aware of academic discourse and debates… but able to make these issues relevant and accessible to a wider readership.1

This is a hybrid borne out of necessity: readers wouldn’t read otherwise.

While this kind of Sunday article is certainly known to us all and makes for an admirable literary goal, these sorts of articles also tend to address subjects that have much richer bodies of classically “critical” writing than graphic design. Since most readers have had some experience with this backlog of criticism, they will be more oriented within a discussion of that subject than they would be in a design discussion, a discipline whose basic principles are largely unknown or poorly understood by others and that has yet to truly define the basic working framework of a criticism for itself.

Finally, this Sunday journalism tends to be practiced by some of the finest writers of our time, the closest thing we have to modern-day public intellectuals, and, in the realm of graphic design, we find quickly that writers of that calibre are in short supply. Along with Poynor, Rock notes that “Most design critics start off as practitioners with a penchant for writing,” adding, “But without seven years of graduate study in preparation of a dissertation to hone their abilities, most design critics have to squeeze in writing here and there, and learn on the fly. Unfortunately it shows.”

This second kind of hybrid, the designer/critic, is also borne out of necessity: design writers wouldn’t exist otherwise. But the problem, Rock notes, is also partly systemic. Design schools, adept at training visual originators, may balk at the cases of students who display above-average verbal abilities, and their classmates may regard them with suspicion, too: perhaps they overcompensate verbally for what they lack visually. In a small community, critics must often write about people with whom they have a personal or social relationship. (For example, Rock was my teacher.) There are too few editors willing to tamper with their publication’s standard array of offerings, and there are too few writers willing to break with form at the risk of losing their audience. And it’s not like you can make a living at it.

Not only is it potentially thankless, but the position of the journalist/critic/designer is also schizophrenic. As a writing designer in Dot Dot Dot, I have published two essays. One covered a contemporary art fair (journalism) through the lens of an academic essay about posters (criticism). Another covered a contemporary composer (journalism) by reviewing his music (criticism) and imagining a possible cover for one of his albums (design). One of these essays was highly principled, critically unambiguous, and observed from a third person perspective. The other was distractedly meandering, impressionistically assembled, and explained from a first person perspective. It was the process of re-examining these two very different essays that led me to thinking about one of the most basic building blocks of any language, critical or otherwise: tense.

I’m pleased to find that I’m not alone. One attribute of an organized criticism is a set of sustained discussions on a key term or idea among several thinkers in the discipline. This way, one thinker can cite another’s way of thinking and reinforce it, correct it, or reject it entirely. In doing so, the uses of an idea common to both of them are expanded to include their collective wisdom. Once a dialogue over a common idea is taking place, the idea itself will lead the discussion and will be amplified and refined by it.

Over the new year I traveled to Paris and happened to discover a book called Dutch Resource: Collaborative Exercises in Graphic Design, which was produced by the students of the Werkplaats Typografie as part of their residency at the Chaumont Graphic Arts Festival in France. Inside, ten students collaborate with ten designers to create a unique presentation of some of the designer’s key projects and texts. These chapters range in tone from academic to folksy, and their design vernacular ranges from that of an antiquated engineering textbook to that of a homemade webpage of remaindered links. These collaborations between designer and designer, one in essence “performing” the identity of another, hints at some of the schizophrenia that the back cover copy makes explicit. “Today’s graphic designer, a specialist and jack-of-all-trades in one” – a hybrid of hybrids! – “who is not only meant to be a good designer but often works as a writer, researcher, editor, curator, critic, and photographer as well.”

Beyond this set of highly specialized roles lies another: type design, motion graphics design, information design, printmaking, art direction, etc. While I would like to try my hand at all of these roles, I do not expect myself to excel at all of them. Quite the opposite, I would assume failure in most of them. And while I was delighted and inspired by Dutch Resource and much of the ambitious work in it, as a critic I take some issue with its overall structure, pairing designer with designer. True, this might mirror an educational model and make for some interesting conversation, but it also seems to suggest that the mere act of collaboration is enough. It isn’t. The best collaborations assume a diversity of their participants’ gifts. The model in Dutch Resource is a wolf in sheep’s clothing, less collaboration among equals and more that of the journalist-subject, or student-teacher, or employee-employer, or designer-client.

The First Person, The Third Person

The beginning of Maxine Kopsa’s introduction, “Semi or Fully Automated,” makes her anxiety over tenses clear: “It’s really quite impossible to write about the Werkplaats Typografie normally. What I mean to say – and I promised I wouldn’t bring myself into this, but look, sentence two, I’m already using the ‘I’…” Is Kopsa a commissioned writer or an independent critic? Is she covering the Werkplaats like a journalist or speaking as one of its designer participants? Where is she sitting, and where are we meant to sit in order to get comfortable? Later, the duo Maureen Mooren and Daniël van der Velden collaborate with Jeffrey C. Ramsey to “re-shuffle, in random order, some things they have previously said about their work – in an attempt to create an ‘oracle’ of text, or simply a resource of words on a profession in need of more explanations.” In creating and defining terms, their aim is like the critic’s, but the multiplicity of their authorship and the recycled nature of their language suggests a kind of artistic assemblage instead.

This three-part invention is reminiscent of another, also documented in the book, between Paul Elliman and the duo Armand Mevis and Linda Van Deursen. The essay “Too Much Information” in their book, Recollected Work, is credited to Elliman, but in reading it one quickly becomes aware that it is the result of a collaboration between the three of them. What is so startling about it is the way that it transforms some of the anxieties over tense that I have described into sharp critical tools whose explanations come from the nature of design and technology itself. Instead of journalistically reporting the facts of Mevis and Van Deursen’s projects and practice, Elliman opts to envelop the duo’s chatty observations in his own narration, borrowing metaphorically from the novelistic convention of free indirect discourse.

Free indirect discourse uses a single narrative voice to assemble and recreate bits of direct speech and indirect observation from multiple sources. Here’s a very simple example: He would love to do it. Were the he to express this thought himself, he might say, in quotes,“I would love to do it.” This is his direct statement, thus direct speech. Direct statements are the only way to know emotional facts like whether or not someone would love to do something. We cannot know unless the person feeling that emotion tells us directly. There are things we know indirectly, and these things are based on observations. Once the subject above has made the direct statement in bold, anyone could say indirectly (and not in quotes) that He said he would love to do it. But to state that He would love to do it neither reports an observation nor assigns a fragment of direct speech to an emotional statement made by the person feeling it. Instead, it uses the authority of a third-person narrator to shift us into a locked consciousness. Moreover, the sentence would not seem the least bit odd if it were written like this: He would love to do it, but she thought he was lazy. However, he has not said directly that “I would love to do it,” nor has she stated directly that “I think he is lazy.” Within a single sentence, we have jumped from one person’s consciousness to another. And it would be easy enough to go back out again: He would love to do it, but she thought he was lazy, even though he got up to leave his chair immediately, while she sat still. And while it is our faith in a narrator that enables this bewildering trick, narrators are not obliged to be solely factual, and in fact they are more than welcome to lie to us at any time. As a result, the use of free indirect discourse as a rhetorical device is ambiguous: it’s not clear if the narrator is speaking for the character, or if the character is speaking for himself.

It may also be, as the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin has observed, that both instances are true simultaneously. In his essay, “Discourse in the Novel,” which Bakhtin wrote during a six-year period of state-imposed exile in Kazakhstan, he writes,

It frequently happens that even one and the same word will belong simultaneously to two languages, two belief systems that intersect in a hybrid construction – and, consequently, the word has two contradictory meanings […].

The idea that a word could belong to two “languages” comes from Bakhtin’s concept of “heteroglossia,” which allows for several subcultural languages (like “business-speak”) to subsist and compete among each other within a national language (like “English”). This means, as Bakhtin observes, “With each literary-verbal performance, consciousness must actively orient itself amidst heteroglossia, it must move in and occupy a position for itself within it, it chooses, in other words, a ‘language.’” Thus every bit of speech is a positioned bit of speech, and every speaker must decide how he is positioned with regard to others before speaking. Bakhtin identifies the concept of heteroglossia as having come from his experiences in the local marketplace where he heard peasants simultaneously retelling stories, bargaining for vegetables, and deferring to the landed gentry. Heteroglossia, then, is a popular phenomenon, and Bakhtin naturally found it flourishing in the then-emerging popular form of the novel. Following an analysis of some passages from Dickens, Bakhtin writes,

Heteroglossia, once incorporated into the novel, […] is another’s speech in another’s language, serving to express authorial intentions but in a refracted way. Such speech constitutes a special type of double-voiced discourse.

When Rock and Poynor title their essay “What is this thing called graphic design criticism” – note that they don’t use quotes – they are both reproducing an overheard direct phrase, “graphic design criticism,” feigning naïveté about this phrase as a rhetorical device, and finally appropriating this phrase as their own in order to define it for themselves.

A combination of Bakhtin’s “Double-voiced discourse” and free indirect discourse also runs throughout Elliman’s “Too Much Information” essay in Mevis and Van Deursen’s Recollected Work. For example, the first sentence of the back cover blurb reads, “The COVER, we always do the cover last, at the end of the project, following decisions taken inside the book.” Presumably this is either Mevis or Van Deursen speaking for both of them in the first-person plural. Then someone says (or writes), “Even though the publisher always wants the cover designed right at the beginning, you know, for those sales catalogues.” First, whoever the speaker (or writer) is, they are freely reporting an emotional fact known only to the publisher. The publisher has not “said” directly that he wanted anything. Upon further inspection, although either Mevis or Van Deursen might have been speaking a sentence or two ago, this following statement could be coming from either one of them or from Elliman, the interlocutor, either egging one of them on in conversation or inserting his critical point of view in the transcript afterward.

This innocent-seeming back-cover blurb, which would probably be frustrating to any publisher, plays subtly with time as well, describing, through a set of blatant contradictions, a time before it even existed in description: “[The COVER] is always easy though; maybe the easiest part of the book. But even in this case we’re not sure what to do with it yet.” These statements could easily be from one speaker in a moment of hesitation or from two speakers in the midst of a friendly disagreement. The design of the book itself speaks to this mixed-up set of identities, presenting distinct projects as if strewn across a tabletop, unaligned, fragmentary, and occurring all at once. The illusion that designers work on a single project at a time dissolves so that the less-organized, more eclectic, more collaborative truth of the studio environment can emerge. Neither projects nor statements have quotation marks to offset them, and readers, like their narrators, must move freely, almost frenziedly, from one item to the next.

In his discussion of “Too Much Information” in Dutch Resource, Elliman points out that the act of typesetting speech functions similarly to heteroglossia and free indirect discourse in the way it blurs the boundaries between who’s saying what, what language was initially speech and what wasn’t, and in what capacity the reproduced phrase is meant to represent or reflect upon the whole. He notes in Dutch Resource that “Here you have a text in which you can’t really distinguish between the written and the spoken word, even when you think you can.” Like the technique of free indirect discourse, the process of typography erases distinctions between speakers, tones of voice, types of subcultural language, and modes of language production. Typesetting is a standardizing affair, and, as Kafka alluded to in “In the Penal Colony,” sometimes a brutalizing act of loss. Elliman adopts another trope from Kafka later in his commentary, that of spontaneously turning into an insect, suggesting to readers who attempt to guess the identity a given speaker that “if you go back to some original recording, or become a time-traveling fly on the wall or bug in the phone you’ll be a bit disappointed.”

Sharing another trick of Kafka’s, Kopsa’s introduction adopts the use of initials for standard terms. Much of the writing from the Werkplaats does this: as Stuart Bailey (my editor for this article) explains in “A note on initials,” from the book In Alphabetical Order, this convention originated because “Full names feel too clumsy, first names feel too informal, and surnames feel to formal.” Initials allow for the “serious informality or informal seriousness I’m after.” But the uninitiated may also recognize initials as tools of anonymity, their provenance exclusively typographic, culled from the world of forms, transcripts, and legal documents. Kafka knew them from his job as an insurance clerk, and, perhaps unintentionally, WT has taken a page from the book of Joseph K.

The Reading Sitter

At the end of his comments in Dutch Resource, Elliman admits that

I’ve got an abiding interest in the relationship between language and technology. My interest in typography is clearly a part of that. But so are questions about the role of text in history. Both historical texts and contemporary texts and the writing of them. The construction of a text.

Here, his hybrid role serves him well: the method and logic of a critical argument is something to be designed, too. The text is being designed by its author as it is undesigning and examining the object that is its author’s concern. I can certainly relate. As I write this, I have two overwhelming sensations: that I should add some kind of parting thought here, and, at the same time, that I should not. One voice is urging me onward, and another is begging me to resist. Earlier I was sitting back, relaxed, voicing observations without any necessary conclusion in mind, but now I find myself having changed positions in my chair. I’m leaning forward, more focused, almost forcing myself to reveal some kind of point here, though I’m not sure that one exists. I’m nearly up out of my chair now, trying to listen to which of these voices is the loudest, but it’s hard to hear if it’s the critic or the designer talking.

-

There is some evidence that Poynor, as critics do, has recently changed his thinking on this front. He writes in the March 2006 issue of Icon Magazine that “criticism and journalism are different activities. While it’s certainly possible for journalism to have a critical intention, most design journalism simply reports the latest news.” I agree, and think that recognizing this, as I have tried to outline above, is a major step in defining our profession’s expectations of the critic. ↩