Form-giving

1. BASKET

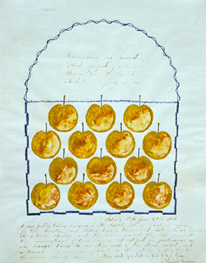

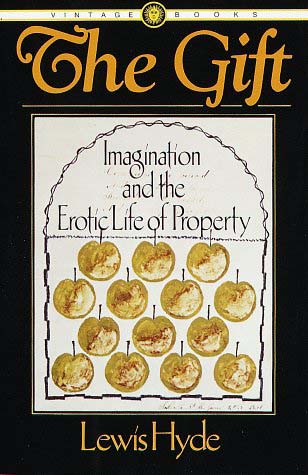

The Gift came, as gifts often do, without my asking for it. Its cover flashed up on my computer screen by way of an Amazon.com server that drew upon a collective memory of what customers like me had already purchased when I logged in one afternoon looking for a particular book on Shaker design. The cover, probably designed in part by The Gift’s author, Lewis Hyde, caught my eye because it featured a drawing that Hyde, who is an English professor at Kenyon College, credits inside as “Basket of Apples.” The drawing, however, is more properly credited as “A Little Basket Full of Beautiful Apples” and was made 150 years ago by a self-taught Shaker woman named Hannah Cohoon, who would have called it a “gift drawing.” I had first seen it several days before, in an article from The New Yorker by Adam Gopnik on the Shakers titled “Shining Tree of Life,” where he describes both the drawing and the circumstances of its making:

Visions and ghosts came down, and the Shakers, chiefly women and young girls, made “gift drawings:” the drawings were gifts from above, not gifts to another. […] One of them, “A Little Basket Full of Apples” (1856), is among the key drawings in American art, with a tonic sense of abundance – all the apples just alike, each with its rub-on of rouge, like blush applied by an adolescent girl – allied to obsessive order.

A few weeks earlier, I’d become interested in gifts after having a vision of my own (or perhaps it was something more like a dream). Waking suddenly one night, I scrawled the following assignment for my students on the back of a New Yorker subscription card by my bed:

Form small groups and spend time together this week. For next week’s class, give a gift to a group member that will evoke an emotional response when given.

I clicked on The Gift’s cover and placed it in my cart. About ten days later, a brown padded envelope arrived in my mailbox at work. Unwrapping it, I found myself facing Hannah Cohoon’s apple basket once again.

2. SPIRIT

Hyde’s book is an inquiry into both the meaning of gifts and the place of creative artists in a commercial society. His first essay begins with an examination of book covers. He writes,

At the corner drugstore my neighbors and I can now buy a line of romantic novels written according to a formula developed through market research. An advertising agency polled a group of readers. What age should the heroine be? (She should be between 19 and 27.) Should the man she meets be married or single? (Recently widowed is best.) […] Each novel is 192 pages long. Even the name of the series and the design of the cover has been tailored to the demands of the market. (The name Silhouette was preferred over Belladonna, Surrender, Tiffany, and Magnolia; gold curlicues were chosen to frame the cover.)

Then comes Hyde’s insightful question “Why do we suspect that Silhouette romances will not be enduring works of art?”, to which he responds,

It is the assumption of this book that a work of art is a gift, not a commodity. Or, to state the modern case with more precision, that works of art exist simultaneously in two “economies,” a market economy and a gift economy. Only one of these is essential, however: a work of art can survive without the market, but where there is no gift there is no art.

What is a gift, and how are gifts distinguished from commodities? Hyde clarifies this: “[A] gift is a thing we do not get by our own efforts. We cannot buy it; we cannot acquire it through an act of will. It is bestowed upon us.” Hyde then invokes the word “gifted,” reminding us that it can be used to describe an individual’s talents, and he explains that talent is also a kind of gift. Intuition and inspiration fall into this category, too, following Hyde’s insight that

As the artist works, some portion of his creation is bestowed upon him. […] Usually, in fact, the artist does not find himself engaged or exhilarated by the work, nor does it seem authentic, until this gratuitous element has appeared, so that along with any true creation comes the uncanny sense that “I,” the artist, did not make the work.

This is the drip, the wrinkle, the tiny imperfection or hiccup in technology that snaps the whole artwork into place. It reminds me of the increasingly popular practice of leaving – or even aestheticizing – mistakes in order to “open up” a piece of work. By admitting the artifice of an artwork, the indefiniteness of a “finished” piece, the artist also admits his own humanity, and, in so doing, empathy may form between the artist and audience. The work of the audience completes the work of the artist, and each is grateful for the participation of the other.

Hyde explains, “Even if we have paid a fee at the door of a museum or concert hall, when we are touched by a work of art something comes to us which has nothing to do with the price.” Often we talk about the “spirit” of a gift – similar to the Shakers’ ghosts and visions – and this spirit passes from the artist through the work of art to society. “The spirit of a gift is kept alive by its constant donation,” says Hyde, adding, “a gift that cannot be given away ceases to be a gift.” So what was once a gift can suddenly become a commodity simply by ceasing to give it away? Yes, says Hyde, warning that “the way we treat a thing can sometimes change its nature.” Art may enter the world through the economy of gifts, but it may also soon change into a commodity. Rather than spreading from one person to the next, the artwork is now confined, corralled, and cordoned-off. It belongs to one person and not another. Removed from circulation, its social power fades to equal that of any other privately-owned good. This is why the most sought-after buyers of art among galleries and dealers are those most willing to lend, showcase, and ultimately give away their prized collections.

3. PRESENT

For a short essay in Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist titled “The Joy of Getting,” Michael Bierut provides a first-hand account of receiving Christmas gifts from Kalman’s renowned New York design firm M&Co:

They seemed to arrive on the same day all over town. Usually, some of the younger designers in my office would see the package with the M&Co mailing label as it arrived, and personally carry it back into the studio. The opening of the package, inevitably an event in itself, was something no one wanted to miss.

The gifts, given annually between 1979 and 1990, became increasingly complex as the years went on, as well as increasingly consistent with Hyde’s formulation of gifts as community-defining objects in constant circulation. As he tries to sum them up, Bierut jokes, “I can’t imagine that any of them resulted in getting business for M&Co,” and, in a literal sense, he is probably right.

The gifts were sometimes banal (cookies and chocolates), sometimes ironic (a plastic paperweight in the shape of a crumpled sheet of paper), sometimes functional (a desk set), and sometimes elemental (space represented by rulers of wood and steel, time by a wall calendar and clock). The gift from 1986, a dictionary, included with it that classic symbol of education, an apple, looking in the photographs like it was plucked from Hannah Cohoon’s basket or maybe off the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden itself. Knowledge, like food, is a gift that circulates freely, brings us together, and is, in the best of times, ever-flourishing.

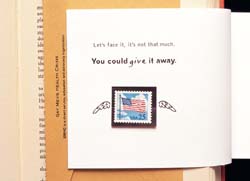

Knowledge is also the frame for M&Co’s penultimate gift, dubbed “the $26 book,” a lesson on the nature of giving itself. According to Kalman, following the toppling of the Berlin Wall in 1989, M&Co had “a change of heart over holiday gift-giving. Instead of trying to outdo the previous year’s present, this year’s bounty would deflate all expectations.” Though he was always a provocateur, I doubt Kalman intended this “deflation” to be as jarring as it sounds. Rather, I suspect, in the light of such a revolutionary, community-restoring global event, Kalman understood that the wall’s destruction was the ultimate gift, not an object of desire but an action that made the world a better place. This is the “deflation” he had in mind: there was great beauty in the destruction of an ugly old wall.

M&Co’s gift followed suit, getting its audience to literally judge a book by its cover. What appeared at first like a dirty second-hand hardcover book had been bookmarked with notes and dollar bills totaling $26, a number that, according to Kalman, was purposely set at $1 over the federal limit on gifts. Since accepting the full amount was essentially a crime, M&Co suggested that recipients give some or all of their bounty away. Kalman observed that

The entire transaction took place inside the individual’s conscience; it was a completely private experience. It was like finding five dollars in the back of a cab and deciding to keep it, or getting too much change in a store. We were interested in exploring those feelings.

Bierut describes the experience of receiving the $26 book this way:

It was transcendent: not just a gift but an experience, combining surprise, humor, pathos, and guilt in an astonishingly controlled sequence. Everyone who received it was invited to feel not just the joy of getting but the joy of giving.

Bierut concludes by observing that Kalman is “the person who has given me more gifts than anyone else outside my immediate family.”

4. LANDMARK

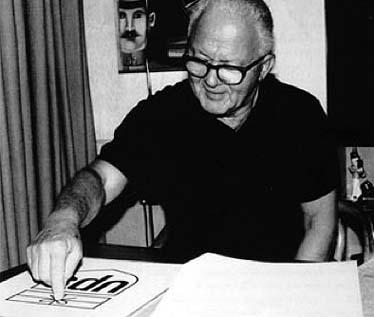

From design critic Steven Heller’s biography of the designer Paul Rand:

Various designers failed to redesign the UPS logo satisfactorily. Rand decided to retain the shield believing that it had symbolic significance for the men who wore it. He replaced the type face and added the “gift” box atop the shield. Before showing his proposal to UPS, he asked his young daughter Catherine, for her opinion – according to Rand, she said: “That’s a present, Daddy.”

While designers churn out new designs every day for clients and seldom get sentimental over them, the disposal of Rand’s 1961 UPS logo in 2003 triggered a reaction throughout the design community – and the culture as a whole – that can only be described as loss. The old UPS logo, in its quiet way, had become something that was almost universally beloved. Writing of this kind of passing, Hyde observes, “The gift is property that perishes. […] The gift that is not used will be lost, while the one that is passed along remains abundant.” Once removed from circulation, Rand’s old UPS logo inevitably wilted and passed away, just like a painting stuffed in the attic.

“It’s sad that this little package couldn’t have survived,” wrote Scott Stowell, a former M&Co designer himself, for Metropolis magazine. In the year following the UPS logo’s demise, Stowell was prompted to write “The First Report of the (Unofficial) Graphic Design Landmarks Preservation Commission,” which put forward the radical idea that certain design icons have reached such a point of cultural recognition and affection that they have ceased to belong to their owners, and should, like beloved buildings, be somehow independently preserved. Many of the designs he recommends for preservation are already in the public domain; only five of Stowell’s recommendations represent private businesses. They are the logos of ABC, NBC, CBS, and UPS, and the former AT&T bell. Not by coincidence, all of these companies are built on communities of ordinary people and are often a fundamental part of our everyday lives. We are the nodes on these companies’ networks, so invariably we feel a sense of ownership over their identities. In allowing them to move through us, we have, even temporarily, made their identities our own, witnessing television signals, phone calls, and packages as they spread from one person to the next, all over the globe.

5. CATALOG

A new image of the globe in 1966 was part of what sparked Stewart Brand to create The Whole Earth Catalog. After launching a public campaign aimed at getting NASA to release their then-rumored satellite image of the earth as seen from space into the public domain, Brand’s liberated globe became a symbol for a publication that Brand described to the Catalog’s young designer J. Baldwin as something “so that anyone on Earth can pick up a telephone and find out the complete information on anything. […] That’s my goal.”

Lecturing at Stanford 40 years later, Apple CEO Steve Jobs described the Catalog as “Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along: it was idealistic, and overflowing with neat tools and great notions.” What merited an item for inclusion in the catalog was its usefulness and accessibility, or, as Brand wrote in his introduction from 1969,

An item is listed in the CATALOG if it is deemed:

- Useful as a tool,

- Relevant to independent education,

- High quality or low cost,

- Easily available by mail.

Always being updated and improved, The Whole Earth Catalog was in a constant state of evolution, much like today’s open-source technologies, passing round and round among its issuers and its audience for improvement. It cost $4. When the Catalog ceased operations in 1971, Brand held a “demise party” at the new San Francisco Exploratorium, giving away $20,000 in cash to promote the extension of the Catalog’s mission. Among the recipients were the then-fledgling Homebrew Computer Club whose early members included young Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. To Hyde, giving to fill a need makes sense not just emotionally but formally. When we give to charity, we do not expect anything directly in return. Again, rather than a linear exchange, a one-for-one, gift exchanges move in a circle, broadening the reach of a community’s resources by seeking recipients for whom gifts have not yet been bestowed. “Where does the gift move?” asks Hyde. “The gift moves toward the empty place.”

Above: Tlingit Chiefs, dressed in full regalia, gathered at a Potlatch ceremony in Sitka in 1904.

6. CEREMONY

The idea of filling an empty place, or celebrating the end of something with a generous gift back to the community, is something intrinsic to gift economies, a kind of giving that Hyde names the “threshold gift” or the “gift of passage,” and we see it with great clarity in the Native American tradition of the potlatch, which is described by that great contemporary open-source technology, Wikipedia, as follows:

Originally the potlatch was held to commemorate an important event such as the death of a high-status person, […] Sponsors of a potlatch give away many useful items such as food, blankets, worked ornamental mediums of exchange called “coppers”, and many other various items.

What these sponsors got back was prestige among their peers. Those that gave a potlatch enjoyed increased reputation and a more highly prized social rank. The more gifts that were given, the more valuable these gifts became and the more respected their givers became. Hyde restates this in terms of commodity markets by saying that “Capital earns profit and the sale of a commodity turns a profit, but gifts that remain gifts do not earn profit they give increase.”

We earn something by our own effort, and earnings cannot be given to others. Profits, too, are generally kept by their earner and any gain in value to profits returns to the earner. The gift economy is the opposite. We cannot earn a gift through our own efforts, it must be given to us. And once we have it, it gains value only when we give it to another member of our community. Value follows the gift rather than remaining with the individual, and an increase in value comes only to the community as a whole. Hyde compares the rise of value in a gift economy to a mathematical vector, defined by its movement and direction. Commodities, on the other hand, stay put.

In terms of the potlatch, the prodigious amount of goods given back and forth between neighboring tribes became a great asset in helping those less fortunate. To borrow from economic terminology, it was a case of “spillover benefits.” Hyde writes an entire chapter on the potlatch, contrasting its rituals to those of a market economy by pointing out that in terms of the potlatch,

Virtue rests in publicly disposing of wealth, not mere acquisition or accumulation. Accumulation in any quantity by borrowing or otherwise, is, in fact, unthinkable [in a gift economy] unless it be for the purpose of redistribution.

In terms of the potlatch, a consequence of this redistributory imperative is the fact that the “coppers” – whose function is purely aesthetic – gain in value as they crack and break with use. A copper that has broken in two is treated not as one but two precious objects, because breaking the gift both represents its past and imagines its future. Once perfect and singular, it has worn through time and constant circulation and, in breaking, its spirit is released and allowed to spread even farther.

7. BOND

An analogue to the community dynamics of the potlatch is those of the scientific community, which circulates knowledge in journals that generally do not pay for their articles. In fact, these articles, Hyde reminds us, are referred to as “contributions,” and the payment for them is recognition, or credit. Among other things, this practice ultimately preserves the structure and collaborative potential of the group.

The more a scientist gives, the more his community knows. The more prestige they give him in return, the more ambitious his work is able to become. We’ve seen that giving a gift creates a bond between two people, and that the obligation of the gift is to give it in turn to another person, and so on. In the process a community is established around the gift, and the very structure of this community guards against the use of the gift for an individual’s financial gain. The individual may receive credit, prestige, notoriety, or power within the community as a result of his gift, but monetary income is out of the question, for it converts the community’s gift into the individual’s profit. We can take our cash elsewhere – Hyde calls it a “medium of foreign exchange” – but prestige has currency only within our professional group. “It is the cardinal difference between gift and commodity exchange that a gift establishes a feeling-bond between two people, while the sale of a commodity establishes no necessary connection,” Hyde notes.

Within the community, Hyde explains that “gifts carry an identity with them and to accept the gift amounts to incorporating a new identity.” He uses “teachings” as his primary example of this, and by “teaching”’ he means lessons that have a transformative power on us, forcing us to see ourselves afresh. This is because gratitude for a gift, as Hyde points out, can only be felt once we have labored to receive it. “[W]ith gifts that are agents of change,” like the recognition of a young artist’s talents by a master,

it is only when the gift has worked in us, only when we have come up to its level, as it were, that we can give it away again. Passing the gift along is the act of gratitude that finishes the labor. The transformation is not accomplished until we have the power to give the gift on our own terms.

To understand this labor in terms of a conventional gift, consider being given a camera for your birthday. If it sits in a drawer, it’s not a gift you may be very grateful for. Only with the investment of your time and energy – your labor – does the camera gain significance to you. The gift of a camera becomes your gift for photography, a gift you might someday share with others. The labor or gratitude applies to any significant gift you’ve been given, from a birthday present to a second chance at life.

8. CALL

An example from Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point underscores the similarity between the “labor of gratitude” and the communication technique of known as the “call to action.” Writing of Howard Levinthal’s experiments at Yale University in the 1960s, Gladwell explains that Levinthal wanted to test the degree to which fear could work as a motivating tool. Levinthal’s experiment involved printing up several booklets about the dangers of tetanus that ranged from a “low fear” version featuring a pleasant, text-only explanation of the disease and its effect, to a “high fear” version, featuring gruesome color photos and a litany of indescribable case studies. While the “high fear” booklets may have convinced more students of the dangers of tetanus, only 3% of the students in the entire study got a tetanus shot. When Levinthal did the study a second time, redesigning each booklet to include a map to the campus health clinic, vaccination rates jumped up to 28% of the entire group. The students had learned about something potentially life-saving, and now they were being asked to act on this knowledge. Even more interesting is the fact that the students that got vaccinated came in equal parts from “high fear” and “low fear” groups. Fear had nothing to do with their decision to get vaccinated, but the map did.

Think about booklets like Levinthal’s that you’ve been given at your own doctor’s office. Like so many objects presented to make us act, these booklets are commonly given free of charge. If we don’t receive something through market exchange, is it possible to think we’ve received it through a gift transaction instead? In being made to “look its best,” there’s arguably a ceremonial aspect involved, but when you’re given something you haven’t asked for in a certain way (like in an elegant box) or by a certain person (like your girlfriend), what you’ve been given carries with it an obligation to at least consider why it’s been given to you. Much is written about how objects are best made, but we’ve thought less about they are best given. How does an object enter into the world? What are our rituals for giving it? What are the responsibilities that commonly come with accepting it?

9. DILEMMA

Rather than call these kinds of responsibilities “work,” Hyde opts to call them “labor,” distinguishing between them by defining “work” as “what we do by the hour,” whereas “labor sets its own pace. “‘We may get paid for it,’” Hyde continues, “‘but it’s harder to quantify.’” Gifts resist quantification, both in terms of profit made and time expended. “The growth [of a gift] is in the sentiment. It can’t be put on a scale.” Hyde quickly demonstrates that this argument has very serious implications. “If a thing is to have market value,” he continues, “it must be detachable and alienable so that it can be put on the scale and compared.” Now, Hyde asks,

Consider the old ethics-class dilemma in which you are in a lifeboat with your spouse and child and grandmother and you must choose who is to be thrown overboard to keep the craft afloat. […] [This is] stressful precisely because we tend not to assign comparative values to those things to which we are emotionally connected.

Hyde follows this hypothetical situation with an actual 1971 cost-benefit analysis by the Ford Motor Company involving the Pinto, where the core equation was “cost of safety parts vs cost of lives lost.” According to Ford estimates, the cost of letting 2,100 cars blow up, creating 180 unnecessary deaths and another 180 injuries was 64% cheaper than fixing an $11 auto part.

The reason the part needed to be switched in the first place – the fuel tank of the Pinto was badly engineered – is a design problem, and calls to mind the 11th of Milton Glaser’s “12 Steps on the Graphic Designer’s Road to Hell,” a collection of hypotheticals intended to serve as a primer on design ethics and morality. The 11th Step asks us to consider, “Designing a brochure for an SUV that flips over frequently in emergency conditions and is known to have killed 150 people.” While we can assume that Ford’s engineers didn’t intentionally design the Pinto’s fuel tank to rupture, once the hazard has been discovered it seems, morally speaking, like it’s Ford’s obligation to fix it. Likewise, while we can assume that most designers wouldn’t knowingly promote a car that was unsafe. Glaser’s hypothetical asks us what we would do once we have that knowledge. The commercialist might be willing to use design to sell the Pinto anyway. But if we consider the offering of such information to be giftlike, then we might regard our own talents for communication as giftlike, too; and therefore we might feel responsible for both laboring toward the gratitude of our own gifts and for our community’s responsible use of them.

* * *

At the 45th International Design Conference in Aspen in 1995, Milton Glaser began a speech by arguing that the axiom “good design is good business” may no longer be useful to designers in explaining the value of their creativity to clients. He returned to the idea of “good design” in his conclusion:

We may be facing the most significant design problem of our lives – how to restore the “good” in good design. Or, put another way, how to create a new narrative for our work that restores its moral center, creates a new sense of community, and re-establishes the continuity of generous humanism that is our heritage.

I now realize, though it scarcely mentions the word “design,” that The Gift is one of the most significant books about design that I have ever read. If the narrative that Glaser requires is one that allows for the community, generosity, and morality of what we do to be restored, I can see no better narrative to use than the only one where the object itself is the mechanism for those connections to be made. I have come to believe that the most powerful economy our profession can come to understand is the economy of gifts, and the most important stories we can tell are those of how our objects travel. Hyde teaches us that gifts must move. The next move is yours.